SAMUEL - Week 3

Okay, we’ve had few weeks of character and theme exploration in the story of Samuel (1&2), so it might be time to think about a textual question, with some substantial implications.

What can be said about the historical David?

Cards on the table time for me; when I studied at Exeter, one of my lecturers was Professor Francesca Stavrakopoulou. More recently, her book God: An Anatomy had a wide release and was quite prominently displayed in Waterstones and other book shops, despite being written by a biblical scholar. But back in my time at Exeter University, Professor Stavrakopoulou found some wider attention by presenting a three part series for the BBC called ‘Bible’s Buried Secrets’, engaging with both archaeological evidence and biblical scholarship. The final episode of this series was called ‘Did King David’s Empire Exist?’, and the essential argument was that there is staggeringly little historical or archaeological evidence for a historical David, and perhaps he did not exist. At the very least, the idea of a Davidic Kingdom seems improbable.

Though she explained to us students that the BBC needed a eye-catching position which was a little more polarising than she might reasonably claim by herself, she did make a habit of teasing some of the more evangelical students in class by dropping little lines in like ‘but David probably didn’t exist anyways…’ I found this both greatly amusing and deeply intriguing.

I tell you this to acknowledge that while this particular question is something that I first had put to me 12 years ago, I recognise that it might be something you have never considered.

My job in this blog post, then, is to try to summarise why some people might come to such a conclusion, look at some other suggestions and think about the idea of a ‘David tradition’ which could be weaved into, or layered on top of, our texts.

What is the evidence for David?

As I mentioned, there genuinely isn’t much historical evidence for David at all. The number one piece of evidence that we know of is the ‘Tel Dan Stele’, a broken stone inscription from the 9th century BCE, discovered in northern Israel, that commemorates a military victory by an Aramean king—likely Hazael of Damascus. Written in Aramaic, it is famous for mentioning the "House of David," making it the earliest known reference, from outside of the Biblical texts, to King David or his dynasty. The use of his name in a royal context (by a foreign enemy) suggests David was remembered as a significant ancestor of Judah’s monarchy by the 9th century BCE—just 100–150 years after he is thought to have lived.

Aside from this, there is the ‘Mesha Stele’ or Moabite Stone, which possibly mentions the House of David again, but the stone itself had been smashed up and later reconstructed so the text, in particular the ‘House of David’ line, is unclear and hard to read.

These two things point towards a Davidic Dynasty, but do not pertain to a Davidic Kingdom necessarily.

There is one fort (Khirbet Qeiyafa) which is involved in scholarly discussions around the idea of a Kingdom and a centralised state, but that is widely contested and inconclusive.

So, we don’t have much – and for a certain type of scholar, who’s interest is largely historical, that leads one to a position of questioning the biblical claims about David, or at least suggesting that evidence cannot attest to them.

What do we do with that information?

Well, the truth of the matter is that there isn’t a substantial amount of evidence for most people in that time period, in that area of the world. We shouldn’t be expecting swaths of records necessarily confirming David’ story.

But there is notably more reliable evidence for a number of key figures in that era, like Omri, who was a 9th century King of Israel, or his son King Ahab, both of whom are well-attested to in Assyrian Records.

So it’s not nothing that David lacks historical evidence.

It is enough, I think, that we ought to hold lightly the stories of David and ask the question of how and why they might have come about.

How and why might they have come about then?

If we start with the history and then approach the texts, rather than try to find history to justify the texts, then we can say that there’s a good enough chance that there was a historical David of some kind. His name popping up in the right sort of area in the right sort of era, once for sure and once fairly likely, gives us reasonable probability that someone called David was significant at that time.

We also know how these societies remember and celebrate leaders – Hagiography, which is a combination of historical biography and various stories, traditions and legends. In this type of writing, we might expect to find hyperbole, exaggeration and propaganda. And so, we could reasonably expect that if there was a leader called David, and he was positively remembered, that accounts of his life would surface which portray him positively. He isn’t the only king in history of whom it would be claimed by the people that they were chosen by God, to do God’s work.

The stories we find of David – runt of the litter picked for greatness, humbled and redeemed, a man after God’s own heart – are not a surprise, and in fact could represent expected narratives about a well regarded leader. These are key themes in the wider biblical narrative.

Recently, I heard a theory (listen for yourself here – I recommend this podcast generally too!) that David might have seized power as a type of ‘Warlord’, who gained the attention of those in power through military force. In this suggestion, the stories of David that we come across become a means of legitimising a King or ruler who didn’t come up the traditional route.

He was not the son of the King, Jonathan was.

But then we get the interesting story in 1 Samuel 23:17 where Jonathan basically gives over his right to the throne to David.

Furthermore, we all know the story of David and Goliath, but fewer people know of 2 Samuel 21:19

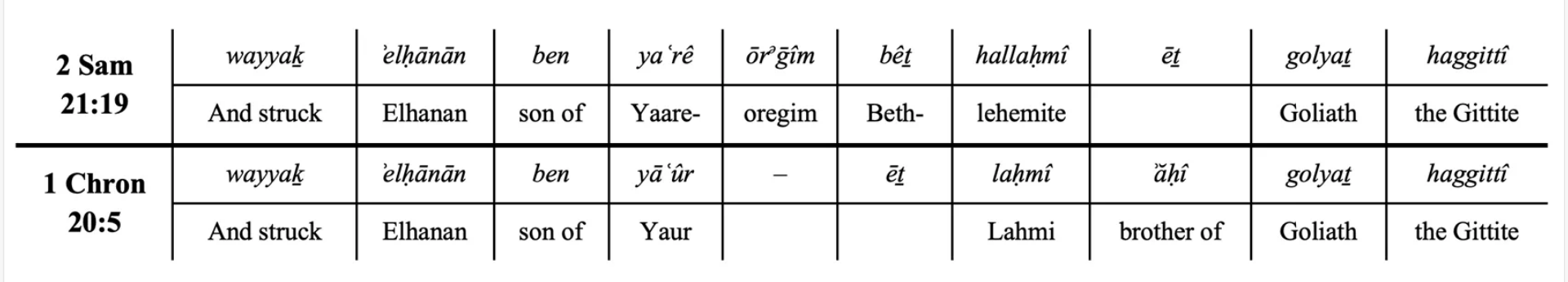

“Then there was another battle with the Philistines at Gob, and Elhanan son of Jaare-oregim the Bethlehemite killed Goliath the Gittite, the shaft of whose spear was like a weaver’s beam”

Huh?!

We later find 1 Chronicles 20 trying to iron things out;

“Again there was war with the Philistines, and Elhanan son of Jair killed Lahmi the brother of Goliath the Gittite, the shaft of whose spear was like a weaver’s beam.”

There are, however, textual and socio-historical reasons to question this reading. Lahmi is a Semitic name, and Philistines at that time wouldn’t have used Semitic names. It is also a name which is not known in the wider area at all. Plus, the Hebrew writing of ‘Lahmi Brother of…’ contains very similar letters to ‘Bethlehemite’ found in 2 Samuel.

Though only English and the transliterated Hebrew, it’s easy enough to see where there is possibility of scribal error. For more on this, you can read an interesting article here.

One proposal is that this is an example of using one story, about Elhanan, and co-opting it to legitimise David as a King with a dramatic, divinely led, victory.

These types of adaptions can be understood as part of a wider ‘Davidic Tradition’ which a majority of Biblical Scholars argue is a later addition to these stories, from an idealised perspective, informed by later theological and political motives.

We looked last week at the story of Saul and the potential layers of tradition, personal and political, which shape his story. The Davidic ‘Tradition’ could work in the same way.

That’s a lot to take on board, I appreciate.

But as we enter into the stories of King David, it’s something to keep an eye out for. Equipped with the knowledge that there isn’t historical confidence in the Biblical portrayal of King David, we can analyse these texts with open eyes and minds.

Where do we see things that look like hyperbole, exaggeration or propaganda?

For balance, I promise that next week I’ll write something nice and friendly about David and these stories…